House Republicans just passed their bill to repeal and replace Obamacare, a plan that reduces taxes but puts millions at risk of losing their health insurance, including people with preexisting conditions, older Americans, and the poor.

The vote on Thursday was close — 217 in favor of the bill and 213 against — and split largely along party lines. (20 Republicans defected to oppose the bill.) No Democrats supported it.

Republicans largely managed to get the bill over the finish line by offering up assurances that it would do things that health care experts say it fundamentally would not, like ensuring coverage for people with preexisting conditions, lowering premiums, and allowing people to maintain their existing coverage. None of these things are true.

Instead, the plan changes key pieces of the Affordable Care Act, allowing states to opt out of provisions that required insurance companies to cover “essential health benefits” and charge everyone the same regardless of their health history. (Vox’s Sarah Kliff has the comprehensive explainer.)

The bill now heads to the Senate, where it’ll face major hurdles to passage. Just as in the House, some hardline Republicans believe the bill does not go far enough and a group of moderates are wary of putting so many voters at risk of losing coverage. The future of Obamacare is uncertain, and it is now in the Senate’s hands.

Republicans in the House still aren’t exactly sure how this bill will affect people or how much it will cost

It took a patchwork of last-minute amendments to bring enough Republicans to a “yes” vote.

So last-minute that House members like Rep. Carlos Curbelo (R-FL) told reporters they still hadn’t read the bill by Wednesday night, just hours before they were expected to vote on it. The House also voted on this bill without a review from the Congressional Budget Office, which estimates how many people the bill covers and how much it would cost.

That didn’t seem to be a big concern for House members, and on Wednesday Rep. Mark Meadows (R-NC) gave assurances that there would be a CBO score before the Senate voted on the bill.

The last time CBO reviewed the bill, the analysis found that the AHCA would increase the number of uninsured by an estimated 24 million people, increase premiums by 15 to 20 percent in 2018 and 2019, and reduce the deficit by $150 billion. CBO has not released an analysis on the latest amendments, which would allow states to waive key Obamacare provisions protecting essential health benefits and patients with preexisting conditions.

Even without CBO’s analysis, for the most part it’s clear how this bill would affect Americans. Vox’s Sarah Kliff broke it down:

Some of Obamacare’s signature features would be gone immediately, such as the tax on people who don’t purchase health care, known as the “individual mandate.” Other protections, including the provision that allows young adults to stay on their parents’ plan through age 26, would survive.

States would have the option to get waivers from two of Obamacare’s requirements: that insurers cover “essential health benefits,” and that they charge the same price to everyone regardless of their health history. That would get rid of a key protection for people with preexisting conditions. An amendment added to the AHCA in late April allows states to opt out of Obamacare’s “community rating” requirement — which says that all people, healthy and sick, should be charged the same prices — for people who do not maintain continuous health insurance coverage.

The Medicaid expansion would be phased out. Before the Affordable Care Act, it was difficult or impossible in many states for low-income adults without children to get coverage through Medicaid. The Affordable Care Act expanded the program to cover adults making up to 133 percent of the federal poverty line ($15,800 for one person, or $32,319 for a family of four), a change that helped drive down the rates of uninsured people in the US. Under the AHCA, the coverage expansion would stay in place until the end of 2019, but no newly eligible people could be added to Medicaid rolls after that. Because people on Medicaid often cycle in and out of the program as their employment situation and incomes change, that would lead to a drop in Medicaid coverage.

The bill would also cut Medicaid in other ways. It changes how the federal government would reimburse states for Medicaid expenses, and introduces the option of states turning the money into a “block grant,” a lump sum rather than a per-person payment for each Medicaid patient, which would cut the program still further. The block grant would ease limitations on states’ ability to kick people off, charge premiums, and cut benefits for children. States, whether or not they take a block grant, could also add a work requirement for non-disabled adults, further limiting access to the program.

The bill would cut taxes for the wealthy. Obamacare included tax increases that hit wealthy Americans hardest in order to pay for its coverage expansion. The AHCA would get rid of those taxes — tax cuts that add up to $883 billion, the majority of them benefiting the wealthy, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Obamacare was one of the biggest redistributions of wealth from the rich to the poor; the AHCA would reverse that.

People buying insurance on their own would get tax credits based on their age rather than their income. Obamacare’s tax credits were based primarily on income (as well as on location, because insurance premiums vary regionally). The AHCA would base tax credits primarily on age, increasing them as recipients get older, and phase them out for individuals making more than $75,000 or families making more than $150,000.

All in all, the replacement plan benefits people who are healthy and high-income, and disadvantages those who are sicker and lower-income. The replacement plan would make several changes to what health insurers can charge enrollees who purchase insurance on the individual market, as well as changing what benefits their plans must cover. In aggregate, these changes could be advantageous to younger and healthier enrollees who want skimpier (and cheaper) benefit packages. But they could be costly for older and sicker Obamacare enrollees who rely on the law’s current requirements.

This was a hard vote for the House. It’s going to be even harder to pass the Senate.

Passing AHCA in the House was difficult. At times, it looked impossible. The House passed it by making concessions to the party’s conservatives, who otherwise were hell bent on stopping the bill in its tracks.

While this will undoubtedly be touted as a big win for the Trump administration and the Republican platform for now, the bill still has a long way to go before it is signed into law — and by the looks of it, it might still be doomed in the process. Already Republicans in the Senate have made it clear that they have a lot of changes in mind, many of which would render the bill more moderate.

For now, that’s the Senate’s problem. But conservative House members are already warning the upper chamber that any drastic changes could kill the bill once it’s sent back to the House.

“I just think if [senators] have eyes to see how tight this thing is,” Rep. Dave Brat (R-VA) said, “if they change more than a iota — they know what they are doing, they are rational, they see what it was like to get to the sweet spot here. Any big changes, I don’t think it will go over too well.”

But it’s clear it will be incredibly difficult to pass this version of the bill in the Senate without changes — and for the exact opposite reason the AHCA was hard to get through the House.

As Vox’s Matt Yglesias explained, Republicans hold slim majorities in both chambers of Congress, and there are vast geographical differences in those majorities. With a bill that can only pass with Republican votes, this puts the majority party in a bind.

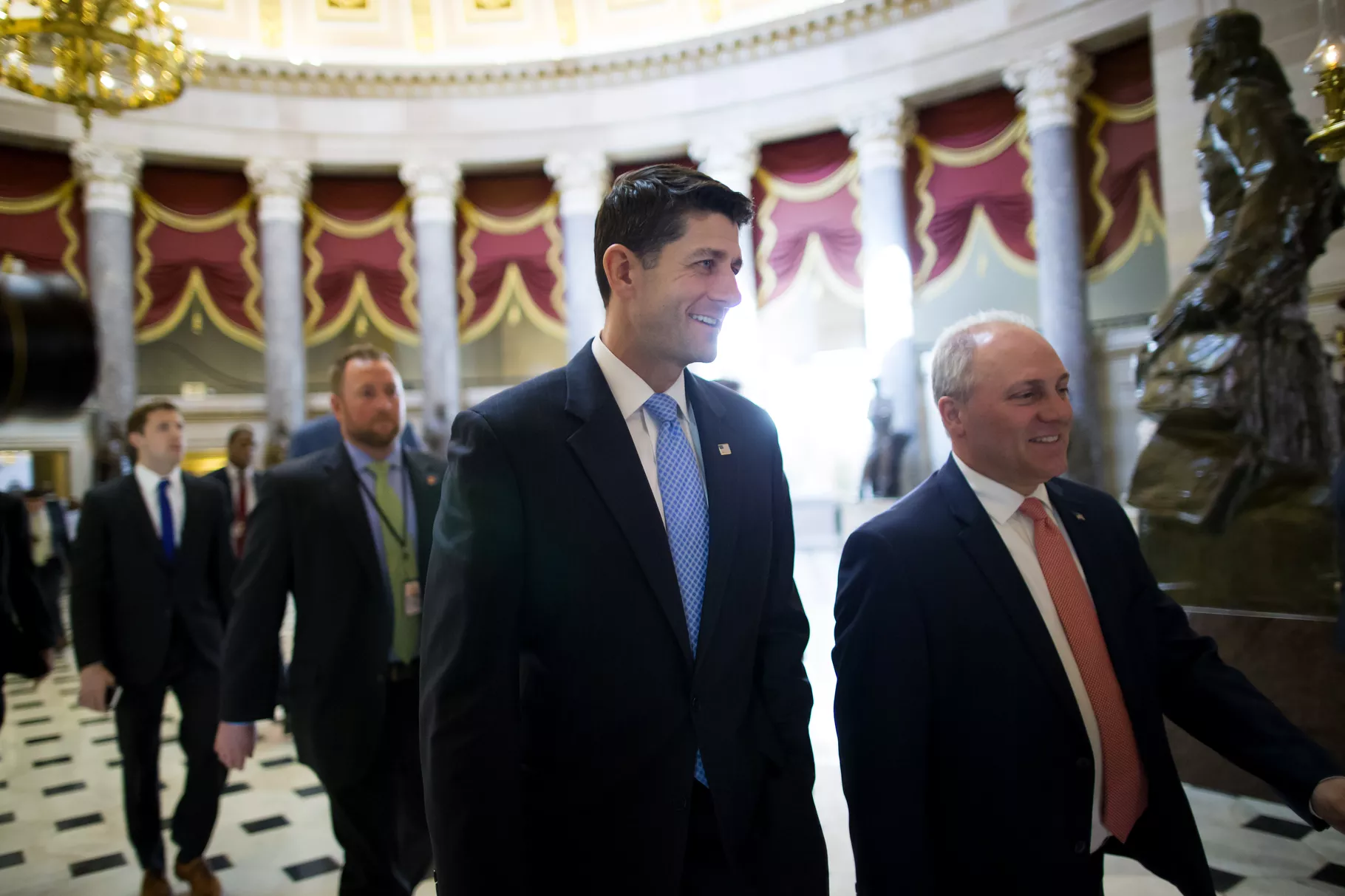

“[Speaker Paul] Ryan, from his perch in an upscale Wisconsin district and ever mindful of the need to corral potential Freedom Caucus rebels, crafted a bill whose passage would be devastating to states that Republicans represent and hope to represent in the United States Senate,” Yglesias writes.

In other words, while the conservatives had the power to shape this health care bill in the House, it’s the moderates, or the members concerned with health care coverage loss, that hold the power in the Senate.

GOP senators like Rob Portman of Ohio, Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia, Cory Gardner of Colorado, and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska have already written to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell with their concerns over Medicaid cuts. Maine Sen. Susan Collins has said any attempt to defund Planned Parenthood (which this bill does) would also lose her vote.

That doesn’t mean the AHCA can’t pass. It just means passing the House was only the first hurdle.